You are viewing our site as a Broker, Switch Your View:

Agent | Broker Reset Filters to Default Back to ListHow iBuyers Die

April 15 2019

iBuyers are all the rage in the investment community. Given the enormously challenging economics of the iBuyer business model, I'm not yet sold that these companies will come to take a large bite out of the real estate pie. What clues can we take from Zillow's traditional and new iBuyer model to peek into the future of the real estate industry inclusive of iBuyers? What can ultimately kill iBuyers?

The Economics of iBuyers

For years, the home buying pie has remained relatively stable. Annually, there are about 5 million homes sold by approximately 2 millions real estate agents (facilitating up to 92 percent of those transactions), which in 2017 generated approximately $80B in commission revenues. With a relatively fixed proportion of home sales to real estate agents, and the fact that the majority of agent commissions are earned by a minority of agents (ignoring team dynamics here), new entrants have always had a hard time competing for a slice. It is not getting any easier for new entrants who wish to shake up the real estate business model as iBuyers intend to do. The economics do not line up well; here are the challenging characteristics:

Low Margins + Highly Cyclical

The pie, when viewed as potential dollars, can always grow simply by increasing home prices (more dollars per commission), but housing is a very cyclical industry, and relatively speaking, the same players are fighting over the same dollar. This is the biggest challenge incumbents face.

iBuyers must rely on massive scale in order to generate meaningful profits due to very slim margins. This requires moving into several markets (50 is the target number I keep reading) to make the model work. This alone requires carries execution risk. While iBuyers have amassed 6 percent market share in Phoenix, across the US currently it's 0.2 percent. As noted below, Redfin currently owns 0.81 percent market share — both a minuscule number for an operation of its size and magnitudes larger than iBuyers today.

This begs the question, "At what size are iBuyers feasible?" and can they actually achieve it? Reliance on funding and market growth do not create sustainable businesses. Even at scale, which brings profits, it also generally affords companies branding power and greater buying power, but as discussed below, it's hard to envision these advantages playing out in this space. Unlike Amazon, iBuyers may not have the velocity and frequency of transactions necessary to develop brand loyalty or dominance in their environment the way Amazon does. Even Amazon's profit margins are slim, averaging between 0–4 percent annually since 2009. With Zillow's margins on its iBuying program generally 0–1 percent and others up to 5 percent, adding the costs of scale, competition, and general fee compression across the industry, there is little room for error to achieve economies of scale necessary for long term success.

Capital Intensive

Looking across the investment capital rounds for iBuyers, it's clear they're a darling of venture capital, and it's fueled fast growth and high valuations. The business of buying and selling homes requires not only near flawless margin management, as mentioned above, but also lots and lots of capital.

This is a similar argument I've made in the past with Compass, which starts to look like a sheep in wolf's clothing when you consider the amount of growth coming from acquisitions, as opposed to growth within the brokerage units themselves. As a gas station operator, there's a difference in growing by buying more gas stations and increasing revenues within your stores. One relies on continued influx of capital, the other arises from truly sustainable competitive advantages. Similarly, just because the gas station owner installs new, fancy ATMs in all its depots doesn't make it a tech company—but I digress.

Hyper-Competitive

As we will discuss below, iBuyers face intense competition not only from other pure iBuyers (i.e., OpenDoor vs. Knock), but from players looking to expand into the space (Keller, Redfin, Zillow, etc.). With a relatively stable pie, the ability to have your fork in different slices can help tremendously, but not as much as one may think (more below).

Take Redfin, for example. According to their most recent public filing, the company has acquired 0.81 percent market share in the US. That's right: 0.81 percent. Redfin's lead generation business is so large they happily refer leads to other non-Redfin agents where they have capacity constraints. How can a company who routinely has hundreds of millions of eyeballs and such lead volume not capture more market share? It's clearly an execution failure — Redfin the technology works well, but Redfin the brand and brokerage do not. Welcome to competitive environment of real estate.

Let's take a deeper look at Zillow, whose recent financial results are very telling for both its traditional lead generation model and iBuyer arm, and helps paint a picture of how iBuyers will live and die.

Zillow's Success and Failure as an iBuyer

For much of the company's history, Zillow has maintained a unique relationship with its customers—agents—in that they near-unanimously hate the company, yet view it as a necessary expense to generate leads. That's because the company has dominated the top-of-funnel sales. What does this have to do with being an iBuyer? I think everything.

Zillow introduced Premier Agent 4.0 in an attempt to move from lead quantity to quality by building a call center to intercept consumers, get them on the phone, and qualify the leads, then routing those leads that are ready to chat with an agent to its Premier Agents. What this did was posit that Zillow could better qualify and nurture leads than agents, and agents did not necessarily agree, resulting in the launch of Premier Agent 4.1 that makes the same interception but passes those leads on to agents who are willing to take them and take on the qualification and nurturing themselves (ironically, back to a quantity over quality position).

The widely-assumed failure of Premier Agent 4.0, I believe, has forced Zillow to strengthen its offerings and competitive positioning by getting closer to the transaction and taking more risky corporate bets.

Zillow Stock Price Last 12 Months (Source: Koyfin.com)

When Zillow announced its acquisition of Mortgage Lenders of America in November 2018, the market looked at the company as divesting from its core business and potentially cannibalizing its core revenue driver, which is bad. On the flip side, Zillow is looking to leverage its brand and de-risk the reliance on a single revenue channel (I would argue their mortgage origination and mortgage lead business are not significant) by expanding.

The question I and other stakeholders are wondering is whether or not these moves are truly strategic or reactionary? Did Zillow see the pressure on its lead-generation machine and make a risky bet it hopes will pay off, or do the blue brass see iBuying as a large enough opportunity to enter?

Zillow has always relied on the traditional commission levels of 5.5-6 percent remaining intact as it better enables their customers to spend on their services. In that sense, Zillow is smart to diversify, given commissions will likely continue to be compressed over time, but is also a participant in that decline by entertaining the iBuyer model so it could effectively be crunching its own core customers' ability to provide the company revenues. Is there a path for Zillow without sacrificing revenues? What if other iBuyers simply died?

How Pure iBuyers Die

At Homebloq, our mission is to build a platform that makes the home buying experience better. We believe this is best done by building technology through the eyes of the consumer, not the broker. With that, we feel strongly that whoever builds a 'thing' that makes the home buying 'experience' better, wins. If that's iBuyers, they win. But here's how, instead, they could lose.

Fail to Maintain Margins

If agent commissions come down, so will iBuyer spreads, meaning the discount at which they purchase the home. It becomes a fast race to the bottom when price-cutting happens. We know the prices and margins will drop — as agent teams, technology, completion, market changes — happen. This is an industry where it's all about scalability. There's a need then to capture revenues elsewhere — which is exactly what Zillow is doing — but this isn't new, and it hasn't been incredibly fruitful. Moving from a relatively commoditized product (houses) to an issuer of capital is incredibly more complex. There is so much purchasing power on the consumer side in mortgage financing, and in aggregate, mortgage markets already have preferred partners, so referrals are not new.

Look at Redfin and their enormous traffic, but miniscule share of the market. There's an execution problem there. How big can a single player get in this industry? Not a lot of this is truly innovative (breaking into different segments, it all exists in different forms).

Become Strictly Buyers of Last Resort

A very likely workflow from a seller's standpoint with iBuyers in the picture is this:

- Get quotes from all iBuyers to know the floor price of accepting an offer

- List the home via FSBO or use an agent

- If step two fails, sell to the iBuyer with the best offer (think of what happens to expired listing leads in this scenario — they disappear).

iBuyers really thrive as the first-choice buyer, where they have more negotiating power. Comparison shoppers carve out that surplus benefiting the iBuyer when they take the offer and can leverage it against the market (as a FSBO), against agents, or against other iBuyers.

This puts so much power into the hands of the consumer that I'm surprised more people are not talking about it. Agents routinely rely on providing home values through CMAs while trashing the Zestimate as only an approximation. What happens when buyers source five offers from iBuyers to establish a floor and create an ultimatum for the agent—beat this price or I sell to the iBuyer. The fact the price represents a real offer negates the argument agents use against the Zestimate that it's flawed and only an estimate.

Of course the floor is not the ceiling. Only the market can dictate what it's willing to pay for the home, but as agent commissions compress and iBuyers' services become more widely known, the iBuyer offers inches closer to a likely sale price. If you think it is annoying when buyers make offers based on the Zestimate, just wait until iBuyers start to price every home by demand in a CMA-like manner and provide that freely to the buyer. I'd like to remind you at this point I am discussing the use of iBuyer's data, not the use of the iBuyer service.

Get Caught in the Tornado of Negative Network Effects

Facebook exploded in popularity due to network effects, which are generated when a platform creates more value as more users join. On the flip side, as more iBuyers come into the space, they're competing against each other for the same dollars, and any first-mover type advantage is washed away.

An interesting irony of iBuyers is the fact that their value-prop strongly relies on eliminating the poor experience and service many home buyers and sellers face. By supplementing this with a streamlined technology, if you're effectively removing much of the 'service' component from the transaction, what you are left to compete on is price.

Push Freemium in the Wrong Industry

A tempting model for iBuyers is to be a loss leader and make it up on services. Just like McDonalds, who takes a loss on the burgers it sells, but makes it up by selling fries, soft drinks, and more—or Gillette, which takes a loss on each razor, but profits handsomely on replacement blades—iBuyers may take losses on buying or selling the home, but instead expand into ancillary services such as mortgage, inspection, repairs, insurance, etc.

A challenge here is in the nature of the real estate business: it's low frequency and has little brand power. The average home buyer doesn't use an agent due to their brokerage or brand—they like that agent. And, as we've seen, as soon as another one comes along, the previous agent is old news. Even services in the real estate industry tend to be less frequent that in industries where this business model thrives. iBuyers will have to garner enormous brand presence to capture repeat service customers. I don't think even the largest players in insurance necessarily want to be in insurance!

Beat to Making Buying and Selling Better

If another technology beats iBuyers to the end game — making the buying and selling experience better — then the iBuyers may not have a compelling enough offer to sustain the type of margins and competitive advantages necessary in a highly cyclical and hyper-competitive market. Similarly, if Keller, Compass, and others pivot hard into iBuying, they can do so with slightly less risk given that they have lead-generation machines, an army of brokers, and more.

If You're Betting in iBuyers, You Likely Would Have Bet on This Company, too. And Not Done That Well.

Let's rewind the clock 10 or so years ago, and I'll tell you about a company in real estate that has a great technology platform geared towards consumers, a team of brokers to assist on either side of the transaction, fees similar to but most often less than traditional agents, and the advantages of bundling services. If you're an iBuyer fan, you're in love with this bet because you see the company easily capturing big time market share.

Of course I'm talking about Redfin.

What's happened since? Redfin has taken the market by storm with that 0.81 percent market share. This gets at the heart of the debate — having all your ducks in a row does not matter if you do not execute. Redfin has a big conversion problem, and one that suggests consumers like the tech, but not the experience enough — and I would argue some of that "experience" may be due to the impression Redfin agents have or, more generally, a level of discomfort dealing with a screen instead of a human. So to solve that, you lean back towards a traditional model that builds off the agent as its core. How effectively can iBuyers balance the necessity of using an agent while maintaining margins only tech-first companies can achieve?

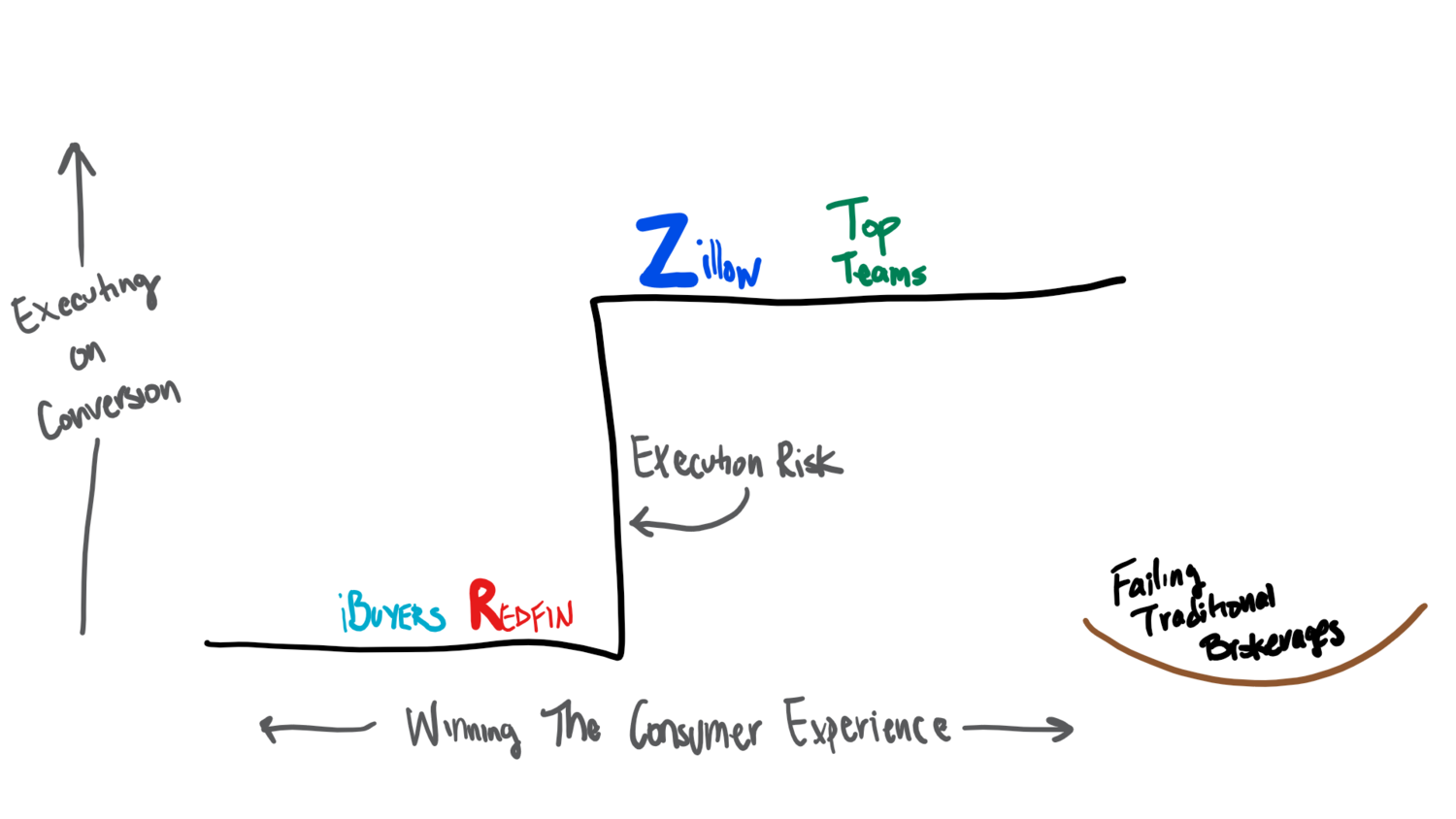

The above in-progress graphic demonstrates the execution risk that Redfin and iBuyers still face. All those in play are providing value to consumers, but only top producing teams (and brokerages) and Zillow are actually converting that value into dollars at scale. Redfin and iBuyers have yet to prove to me their model truly works in terms of delivering real, recurring, and sustainable competitive advantages. The ability to climb up the wall is what really matters when assessing these alternative business models.

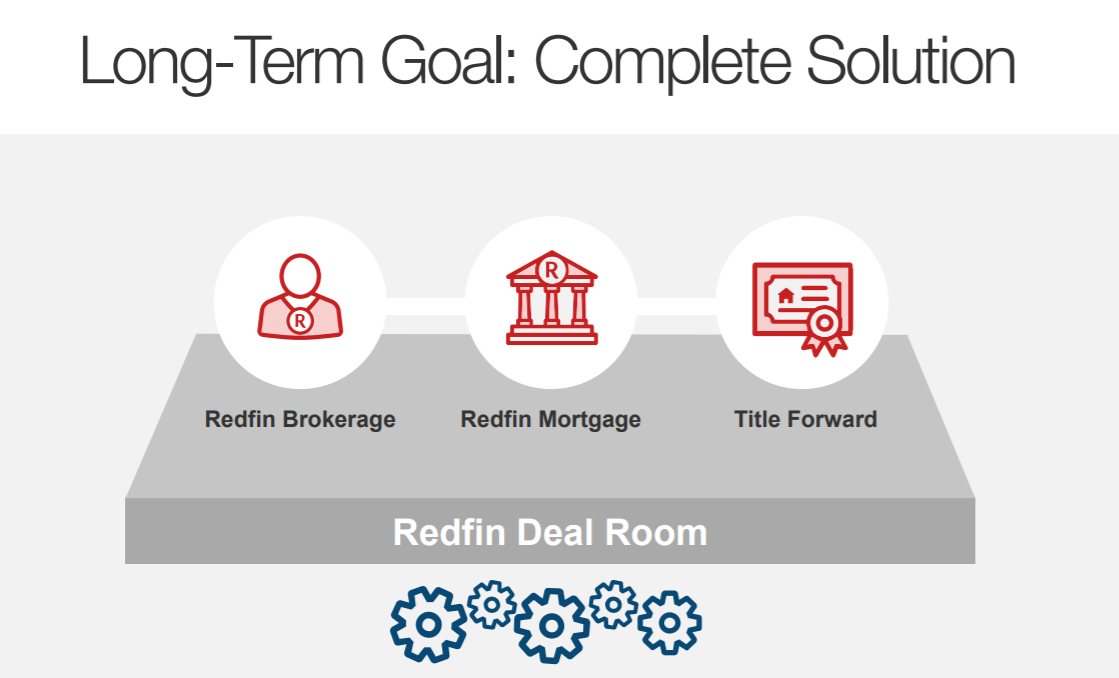

Source: Redfin's Investor Deck

Redfin's long term plan of bundled services and aforementioned tech lineup sound great in theory, but I do not see how they're delivering on their returns to investors.

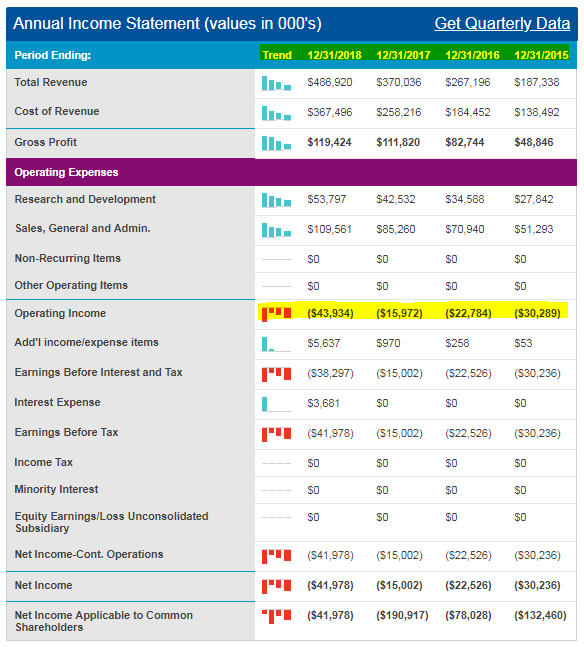

Redfin Financials (Source: NASDAQ.com)

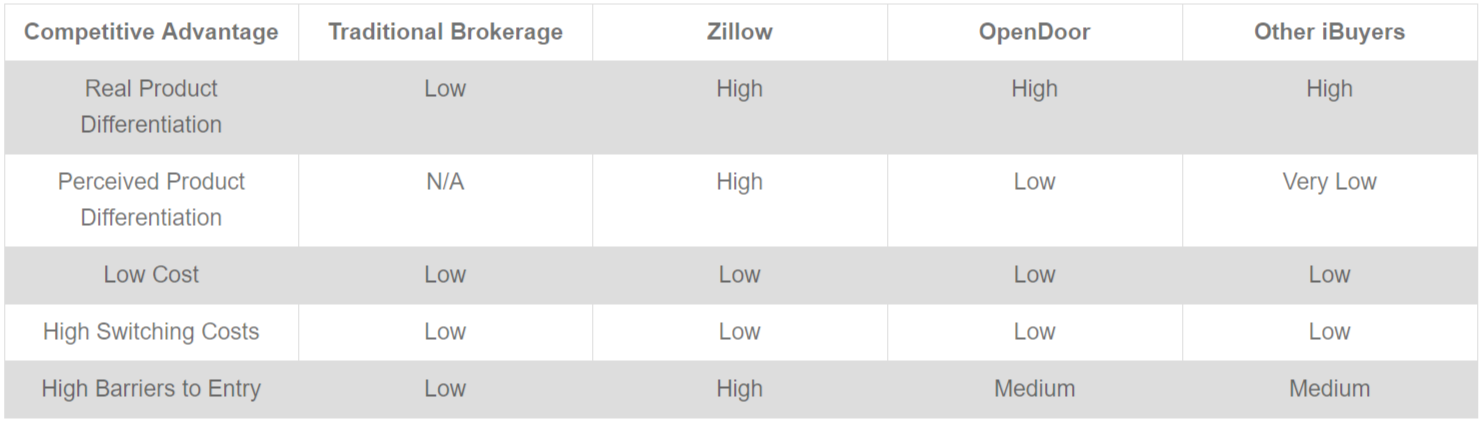

Tallying Up the Score

When assessing companies from an economics and investment perspective, it is important to identify the competitive advantages the company may have. I generally refer to this as the competitive moat the firm builds around its castle. There are five keys to developing such a sustainable competitive advantage:

- Creating real product differentiation through innovation in business model and/or superior technological features

- Creating perceived product differentiation through brand or reputation

- Offering a lower cost product to similar competitors

- Locking in customers through high switching costs

- Locking out competitors through high barriers to entry

Real Product Differentiation

This is the most obvious of competitive advantages. If you build something better than what exists, you win, right? Not necessarily. Better features and design are hard to sustain when all you're doing is building a better mousetrap.

Furthermore, firms that offer premium products must charge premium pricing, limiting the size of their addressable market. These factors make consistently staying ahead of your competition challenging.

iBuyer: There is real innovation happening in the iBuyer space with both technology and changes to the business model that better serves consumers (a must). However, these are hard to sustain as advantages between players in the space. It's not a coincidence iBuyers are launching in markets such as Phoenix, where homes are similar in structure and markets are less differentiated than say, Chicago. How easily can you replicate your model as the complexity of markets grows?

Perceived Product Differentiation

A strong brand can do a lot of good for companies. Most shoppers know that private label products are just as good as the name brands, but they simply do not trust them. This is the essence of perceived product differentiation — if you can create value through your brand, you can sell essentially the same product to more people.

iBuyer: This advantage swoons for Zillow, partially for Redfin (although I'd argue much less so), and certainly represents an advantage for the former over pure iBuyers such as OpenDoor and Knock. I'll echo back to the point that Redfin is for anyone buying a home a household name, but has yet to take anywhere near a commanding market share. Brand loyalty in real estate, or any infrequent transaction industry is hard to develop and leverage.

Low Cost

This is where things get interesting. In commoditized industries such as airlines, where the flight experience is relatively homogenized, firms need to compete on price. This advantage tends to more naturally arise in less competitive industries, like the aforementioned airlines and utilities, because in order to scale, it often requires becoming a loss leader or driving down your own prices.

iBuyer: There are many angles here to play — if iBuyers continue to grab (pieces of) the transaction, one of two things will likely happen to agents: commissions will fall or agents will exit the market. In either situation, yes, iBuyers continue to take market share, but are forced to compete again on fees among each other. This results in negative network effects: when more players that enter the marketplace platform reduce the ability to extract value. This is likely the most complex discussion in this space and I'm looking forward to continued research, so stay tuned.

High Switching Costs

High switching costs are the holy grail of SaaS companies. Is it technically easy to switch CRMs or your bank account? Yes. Is it worth the time and effort? Generally not. How about upgrading your MLS vendor? Woof. These discussions are music to the ears of companies attempting to gain an advantage through high switching costs.

iBuyer: Eric Wu, the founder of OpenDoor, has suggested in the past that iBuyers may need to be loss leaders on the actual transaction, and instead make money on services. For one, I do not envy a company who operates in a hyper-competitive environment (and cyclical) who feels in order to carve out a sustainable advantage, it needs to enter more markets. Even if successful, high switching costs from existing home insurance providers, financing options, and status-quo biases when it comes to financially complex and emotional processes make those within the industries already face challenges.

High Barriers to Entry

The ever-talked about 'network effects' finally come into play. Whether it's a necessity to raise substantial amount of capital, acquire land, or steal users, new entrants facing those with lots of any of that stuff make it challenging to put up a fight.

iBuyer: This is unfortunately again both an advantage for incumbents, but also a disadvantage to those that don't rhyme with pillow. Why does big Z have a comfy advantage? They've already acquired and perfected the lead flow. That's not the hard part — just ask OpenDoor and others who have figured out the workflow portion well enough to get off the ground. Zillow also has substantial capital to play around with and a machine to monetize its site traffic.

The Scorecard

Let's tally this up. It's not looking great for iBuyer economics. Again, there is so much here to discuss that we've not yet covered. What if agents choose to eliminate dissemination of listings to iBuyer sites? What if Amazon acquires OpenDoor? What if a recession hits and wipes out the cash accounts and strangles profit margins for long enough to bleed out the iBuyers? What if I'm flat-out wrong?

This is such an open-ended question because, over the long term, if iBuyers are successful in taking sides of transactions, then traditional real estate brokerages and their agents lose. This eerily is familiar to the genesis story of Zillow — agents created a consumer-facing portal and agents dismissed the threat of new entrants instead of embracing the idea—and bang, Zillow was born and expanded wildly. Will this time around be different?

Zillow, OpenDoor, Redfin and others have carefully placed their offerings as complements to agents, rather than substitutes, allowing agents to keep the mantra that "nothing will replace an agent through an (emotionally) complex process" going. As alternative offerings provide transparency, speed, ease, and data-driven tools to consumers, however, it's harder to buy-in that the advantage agents have with pocket listings, local insights, and negotiation skills will be maintained. This is especially true if iBuyer fees can successfully fall in line with agent commissions.

The above has been an argument about what environment may persist that could kill iBuyers, but could it simply be the case that if agents continually ignore these threats and fail to improve their service offering throughout the transaction it will be a self-fulfilling prophecy that leads to agent expertise no longer being required?

To view the original article, visit the Homebloq blog.